An Introduction to Codemods

Refactoring JavaScript with JavaScript

Refactoring is an inevitable part of software development. As your project grows and requirements change, you will eventually run into problems with your system design. When that happens, you can either waste a lot of time cleaning up old code, or leave things as they are for a bit longer – knowing, if you’re being really honest with yourself, that it’ll deteriorate your code base even more in the long run.

When working on large scale projects, refactoring becomes an even bigger problem. You can no longer make sweeping changes across your code base in one sitting. Also, you become increasingly less confident you’re not making mistakes, and inevitably hinder other developers in the process.

Luckily, it doesn’t have to be like this. While refactoring itself is unavoidable, it is possible to make it a less risky and more efficient process. Just like with automated tests and deployments, you can work faster and with more confidence when refactoring is no longer a manual task. In this post, I’ll show you how to use metaprogramming to automate the refactoring of your code.

Refactoring on massive scale

Let’s take a look at a simple yet common scenario. A function is renamed, and we need to update the identifier in our code:

import {

- foo

+ bar

} from './myLib.js'

// ...

- foo()

+ bar()

In this case, you could simply use a find-and-replace tool to update the name through your entire code base. But! What if we look at a more complex example: consider a class with a property assignment in its constructor. If you are familiar with React, you might recognise this pattern to define the initial state for your component:

class MyComponent extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = { isOpen: true }

}

}

Now, we might decide that we don’t like this way of defining the state, and wish to start using class properties instead:

class MyComponent extends React.Component {

state = { isOpen: true }

}

The change we want to make to this code is straightforward for a single component. However, how are we going to apply this change automatically across 1000’s of files, without the risk of breaking half of your application?

When you treat your code as text, there is no proper way to find and update these structures. The reason for this is that you are missing the semantic meaning of the code; your find-and-replace tool does not know what the code means, it can only see how it was written down.

Abstract Syntax Trees

If it is text-based tools that are holding us back, the way forward is to start looking at your program as structured data. How do we do this, then? By analysing the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) behind your code.

The AST is a structural representation of the syntax of your code. It contains all the information needed to understand what your program should do. This means it can be used to minify your code (without altering the functionality), interpret it, transpile it to another language, or even modify the code in a powerful way.

If you are a JavaScript developer, chances are that you are already using tools that rely on the AST to do their magic: Babel, ESLint, Prettier, and many more wouldn’t be as powerful as they are if they would treat your program as plain text. All these tools will first parse your code to convert it to a format they can reason about and, most importantly, a format that captures the meaning of your code more accurately – rather than the presentation of it.

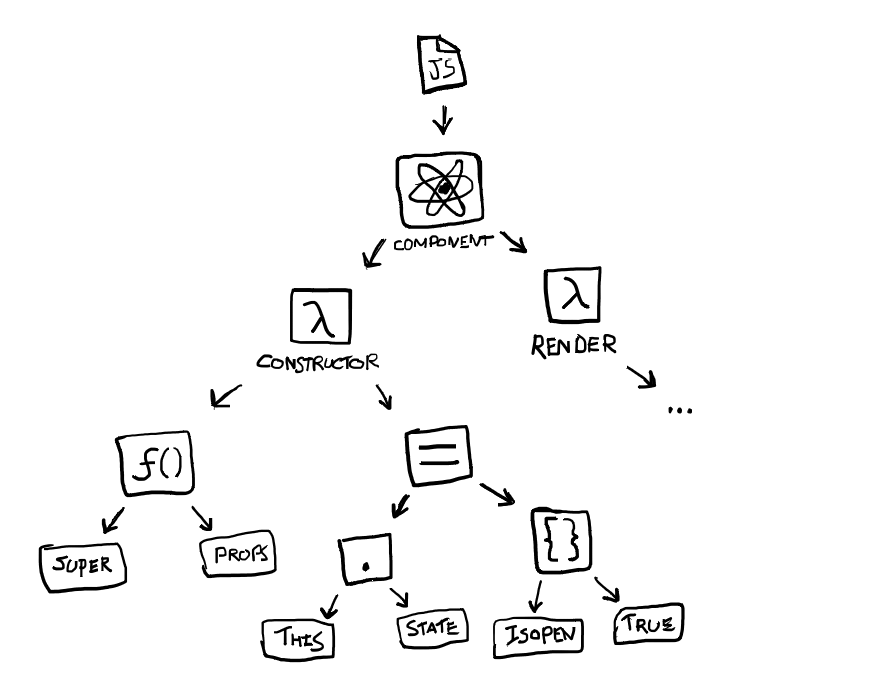

So, what does an AST look like? Take a look at the following tree that represents the code we want to refactor:

At the top of the tree is a node representing the full program. This node has a body, containing all the top-level statements you wrote down (in this case, only the React component). Going deeper, every statement has other sub-children representing code that is a part of that node (the constructor and render method), and so on and so on.

Projects like AST explorer help visualise the AST, and by being able to filter and collapse nodes, make it easier to navigate it as well. These trees are quite large, and you wouldn’t want to work with them manually too much. However, they contain all the information you need to understand what your program is supposed to do, and also convert it back to the original source code.

Code Transformations

Now that we have access to the semantic meaning of the code, we can take things a step further by treating your code as data for another program: metaprogramming. We can use this to write powerful program transformations, also known as codemods, that will automatically modify our source code for us.

To get started quickly, we can make use of jscodeshift. This package provides a useful API that help you write codemods, and a CLI tool to apply them to your code base.

Let’s look at a basic transform function:

export default function transform(file, api) {

const j = api.jscodeshift

const root = j(file.source)

// ...transform root

return root.toSource()

}

The transform function receives the file you are transforming, and the

jscodeshift api as arguments. Calling api.jscodeshift on a piece of

JavaScript code will return a (wrapped version of) the AST that belongs to it.

This object can be analysed and modified, after which you call the toSource()

method to generate the corresponding JavaScript code.

This transform function doesn’t change your code, so let’s look at our previous refactoring scenario. Here, we wanted to replace the state assignment in the constructor with a class field declaration.

class MyComponent extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = { isOpen: true }

}

}

The first thing we need to do is find out where the state property is

initialised. Using AST explorer, you can find out that the node we’re looking

for is located at ClassDeclaration › MethodDefinition[constructor] ›

AssignmentExpression[this.state]. We can select this node using the find()

method on the root, and specify the properties it should match:

export default function transform(file, api) {

const j = api.jscodeshift

const root = j(file.source)

root

.find(j.ClassDeclaration)

.find(j.MethodDefinition, { kind: 'constructor' })

.find(j.AssignmentExpression, {

left: {

object: j.ThisExpression,

property: { name: 'state' },

},

})

return root.toSource()

}

Now that we found the correct node in our program, we continue with the transformation itself:

export default function transform(file, api) {

const j = api.jscodeshift

const root = j(file.source)

root

.find(j.ClassDeclaration)

.find(j.MethodDefinition, { kind: 'constructor' })

.find(j.AssignmentExpression, {

left: {

object: j.ThisExpression,

property: { name: 'state' },

},

})

.forEach((stateAssignment) => {

const initialState = stateAssignment.node.right

const asProperty = j.classProperty(

j.identifier('state'),

initialState,

null,

false

)

j(stateAssignment)

.closest(j.ClassBody)

.get('body')

.insertAt(0, asProperty)

j(stateAssignment).remove()

})

return root.toSource()

}

We get the initial state value (node.right) from the stateAssignment node,

and use it to create a new classProperty node, which is inserted at the top of

the closest ClassBody (in other words: at the top of the class we’re currently

in).

Applying this transformation to our code gives us almost what we wanted:

class MyComponent extends React.Component {

state = { isOpen: true }

constructor(props) {

super(props)

}

}

The state assignment has indeed moved to a class field, but now we are left with a practically empty, not to mention redundant, constructor. We could go back to our transformation to handle this specific edge case, but considering that this might happen often, we can simply create a second transformation to apply after applying the state-assign-to-class-property transform.

Since the transformations are pure functions, it is easy to compose multiple transformations together and reuse them across each other:

export default function transformer(file, api) {

const j = api.jscodeshift

const root = j(file.source)

root

.find(j.ClassDeclaration)

.find(j.MethodDefinition, { kind: 'constructor' })

.forEach((constructorDefinition) => {

const nonSuperCalls = j(constructorDefinition)

.find(j.BlockStatement)

.get('body')

.filter((x) => {

const isSuperCall =

x.node.type === 'ExpressionStatement' &&

x.node.expression.type === 'CallExpression' &&

x.node.expression.callee.type === 'Super'

return !isSuperCall

})

if (nonSuperCalls.length === 0) {

j(constructorDefinition).remove()

}

})

return root.toSource()

}

And there you have it! You’re able to clean up your entire codebase without the effort involved in manual refactoring. Regardless of the amount of code you’re dealing with, you can apply the refactoring in a single, atomic commit. This makes sweeping changes less prone to conflicts, and helps increase the confidence level of large scale refactorings.

Takeaways

But before you go ahead and use codemods for everything, keep in mind that JavaScript is messy. Writing a codemod can take forever if you try to account for every possible edge case in your code. It’s better to see codemods as an assistive tool rather than something magical that will solve all your problems: let it do most of the heavy lifting for you, then verify the diff and make manual changes where needed.

That being said, learning to write codemods basically gives you refactoring superpowers. Apart from impressing co-workers and clients, you are able to update legacy code that nobody wants to touch, and make big changes to the code base that would otherwise take considerable time, effort, and are too risky to do manually. This ability also allows you to postpone big technical design decisions, because your code becomes less permanent and can still be confidently refactored later.

If you want to dive deeper into codemods, there are a couple of repositories such as cpojer/js-codemod and reactjs/react-codemod that include solid examples that can help you get started.

Originally posted on the Reaktor blog